Welcome back. For those of you just joining us, I ended Part I where Stafford Beer’s Designing Freedom begins, in a “little house… in a quiet village on the western coast of Chile”. With the benefit of hindsight and history, we now know that Beer was describing the town of Las Cruces — but we’ll get to all of that, in the fullness of time.

In rapid order, Beer deploys this pleasant coastal scene as grand metaphor, introducing what will form the central thesis of the lectures that follow:

Although we may recognize the systemic nature of the world, and would agree when challenged that something we normally think of as an entity is actually a system, our culture does not propound this insight as particularly interesting or profitable to contemplate. Let me propose to you a little exercise, taking the bay I am looking at now as a convenient example. It is not difficult to recognize that the movement of water in this bay is the visible behaviour of a dynamic system: after all, the waves are steadily moving in and dissipating themselves along the shore. But please consider just one wave. We think of that as an entity: a wave, we say. What is it doing out there, why is it that shape, and what is the reason for its happy white crest? The exercise is to ask yourself in all honesty not whether you know the answers, because that would be just a technical exercise, but whether these are the sorts of question that have ever arisen for you. The point is that the questions themselves — and not just the answers — can be understood only when we stop thinking of the wave as an entity. As long as it is an entity, we tend to say, “Well, waves are like that”: the facts that our wave is out there moving across the bay, has that shape and a happy white crest, are the signs that tell me “It’s a wave” — just as the fact that a book is red and no other colour is a sign that tells me “That’s the book I want”.

The truth is, however, that the book is red because someone gave it a red cover when he might just as well have made it green; whereas the wave cannot be other than it is because a wave is a dynamic system. It consists of flows of water, which are its parts, and the relations between those flows, which are governed by the natural laws of systems of water that are investigated by the science of hydrodynamics. The appearances of the wave, its shape and the happy white crest, are actually outputs of this system. They are what they are because the system is organized in the way that it is, and this organization produces an inescapable kind of behaviour. The cross-section of the wave is parabolic, having two basic forms, the one dominating at the open-sea stage of the wave, and the other dominating later. As the second form is produced from the first, there is a moment when the wave holds the two forms: it has at this moment a wedge shape of 120°. And at this point, as the second form takes over, the wave begins to break — hence the happy white crest.

Now in terms of the dynamic system that we call a wave, the happy white crest is not at all the pretty sign by which what we first called an entity signalizes its existence. For the wave, that crest is its personal catastrophe. What has happened is that the wave has a systemic conflict within it determined by its form of organization, and that this has produced a phase of instability. The happy white crest is the mark of doom upon the wave, because the instability feeds upon itself; and the catastrophic collapse of the wave is an inevitable output of the system.

I am asking “Did you know?” Not “did you know about theoretic hydrodynamics?” but “did you know that a wave is a dynamic system in catastrophe, as a result of its internal organizational instability?” Of course, the reason for this exercise is to be ready to pose the same question about the social institutions we were discussing. If we perceive those as entities, the giant monoliths surrounding pygmy man, then we shall not be surprised to find the marks of bureaucracy upon them: sluggish and inaccurate response, and those other warning signs I mentioned earlier. “That is what these entities are like”, we tend to say — and sigh. But in fact these institutions are dynamic systems, having a particular organization which produces particular outputs. My contention is that they are typically moving into unstable phases, for which catastrophe is the inevitable outcome. And I believe the growing sense of unease I mentioned at the start derives from a public intuition that this is indeed the case. For people to understand this possibility, how it arises, what the dangers are, and above all what can be done about it, it is not necessary to master socio-political cybernetics. This is the science that stands to institutional behaviour as the science of hydrodynamics stands to the behaviour of waves. But it is necessary to train ourselves simply to perceive what was there all the time: not a monolithic entity, but a dynamic system; not a happy white crest, but the warning of catastrophic instability.

— Stafford Beer, “Designing Freedom”, p. 2-3 [emphasis mine]

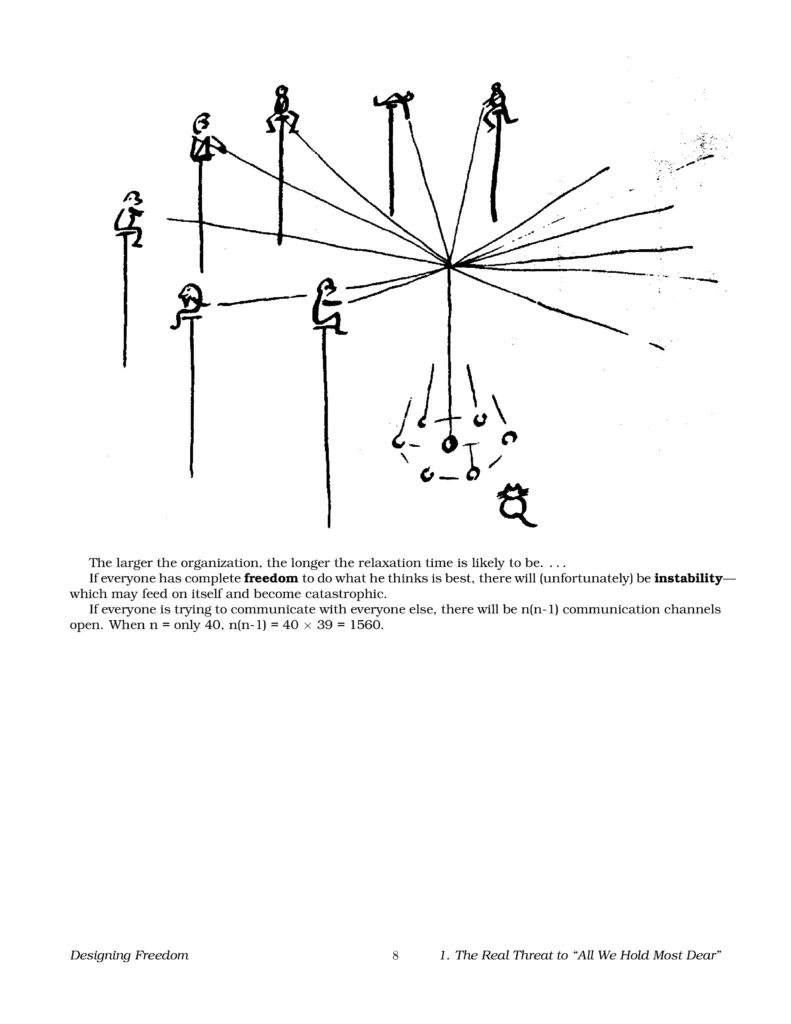

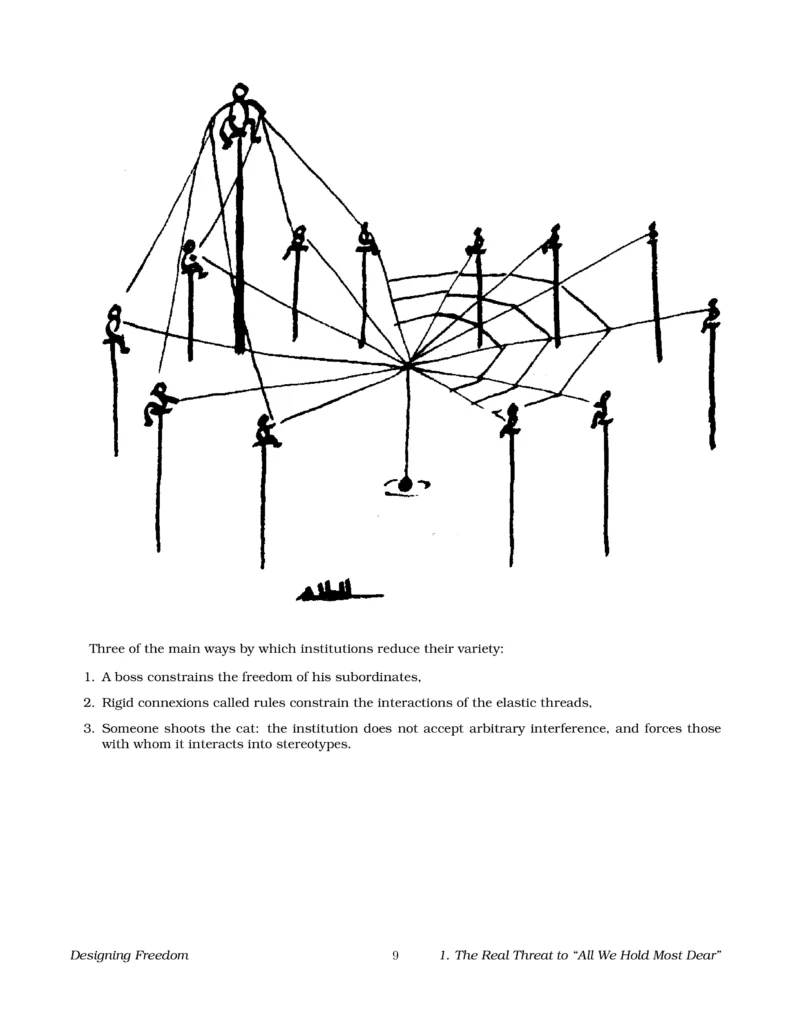

Earlier, I had also shared a doodle from Beer’s “Notes in Support of the First Lecture”, depicting several people sat atop of several poles. Don’t worry, Beer has plenty more doodles like it in his lecture notes (and here they are!):

I bring them up again here as preface to this next excerpt, from the conclusion of Beer’s first lecture:

Remember these aspects of our work together so far. A dynamic system is in constant flux; and the higher its variety, the greater the flux. Its stability depends upon its net state reaching equilibrium following a perturbation. The time this process takes is the relaxation time. The mode of organization adopted for the system is its variety controller. With these points clearly in our minds, it is possible to state the contention of this first lecture with force and I hope with simplicity. Here goes.

Our institutions were set up a long time ago. They handled a certain amount of variety, and controlled it by sets of organizational variety reducers. They coped with a certain range of perturbations, coming along at a certain average frequency. The system had a characteristic relaxation time which was acceptable to society. As time went by, variety rose — because the relevant population grew, and more states became accessible both to that population and to the institutional system. This meant that more variety reducers were systematically built into the system, until today our institutions are nearly solid with organizational restrictions. Meanwhile, both the range and the frequency of the perturbations has increased. But we just said that the systemic variety has been cut. This produces a mismatch. The relaxation time of the system is not geared to the current rate of perturbation. This means that a new swipe is taken at the ball before it has had time to settle. Hence our institutions are in an unstable condition. The ball keeps bobbing, and there is no way of recognizing where an equilibrial outcome is located.

If we cannot recognize the stable state, it follows that we cannot learn to reach it — there is no reference point. If we cannot learn how to reach stability, we cannot devise adaptive strategies — because the learning machinery is missing. If we cannot adapt, we cannot evolve. Then the instability threatens to be like the wave’s instability — catastrophic.

I said before that there are solutions, but I have also shown that they concern organizational modes. They concern engineering with the variety of dynamic systems. By continuing to treat our societary institutions as entities, by thinking of their organizations as static trees, by treating their failures as aberrations — in these clouded perceptions of the unfolding facts we rob ourselves of the only solutions.

— Stafford Beer, “Designing Freedom”, p. 5-6 [emphasis mine]

Taking Care of Bigness

Speaking of “a dynamic system in catastrophe, as a result of its internal organisational instability”, let’s return to the subject of the modern, commercial Internet. To borrow another turn of phrase from Beer, here are just some of the “happy white crests” of online advertising today:

Show the baby, show the baby! See?! Show your baby.”

1: Ad Fraud

Fraud remains endemic to, and rampant throughout, the online ad supply chain to the extent that one can safely assume that roughly ten cents out of every dollar budgeted towards digital media spend will end up in the pockets of fraudsters – that is, criminal and/or terrorist networks. More conservatively, an advertiser may only be losing a nickel out of every ad-spend dollar to such frauds… but it could just as easily be a quarter, and possibly more. But here I feel I ought to pause (already!), and bolster those claims a bit:

- In June 2016, the World Federation of Advertisers published its “Compendium of Ad Fraud Knowledge for Media Investors“, which found that “[t]he cost of ad fraud is estimated at $7.2 billion in this report, or approximately 5%, of the total global”, and grimly predicted that “ad fraud will, on the current trajectory, be second in revenue only to cocaine and opiates by 2025 as a form of crime.”

- The “2018-2019 Bot Baseline Report“, by the Association of National Advertisers and cybersecurity firm WhiteOps, claimed that “[w]e project losses to fraud to reach $5.8 billion globally in 2019”, and that “[t]oday, fraud attempts amount to 20 to 35 percent of all ad impressions throughout the year, but the fraud that gets through and gets paid for now is now much smaller”.

- A 2023 report by Juniper Research forecast that “the global potential advertising spend lost to fraud will rise from $84 billion in 2023 to $172 billion by 2028”. It further claimed that “North America will account for the highest proportion of advertising spend lost to fraud over the next five years”, and that “[i]n 2023… 17% of clickthroughs on PCs and desktops were illegitimate and could not provide ROAS [return on ad spend]”.

- It should be noted that the same firm had previously estimated the cost of ad fraud, as of 2019, at $42 billion, while projecting that this figure would reach $100 billion as of the year 2023. This would place their starting estimate well above the contemporaneous ANA/WhiteOps report, and suggests that their previous analysis relied on perhaps-overly pessimistic models of the rate of growth in digital ad fraud.

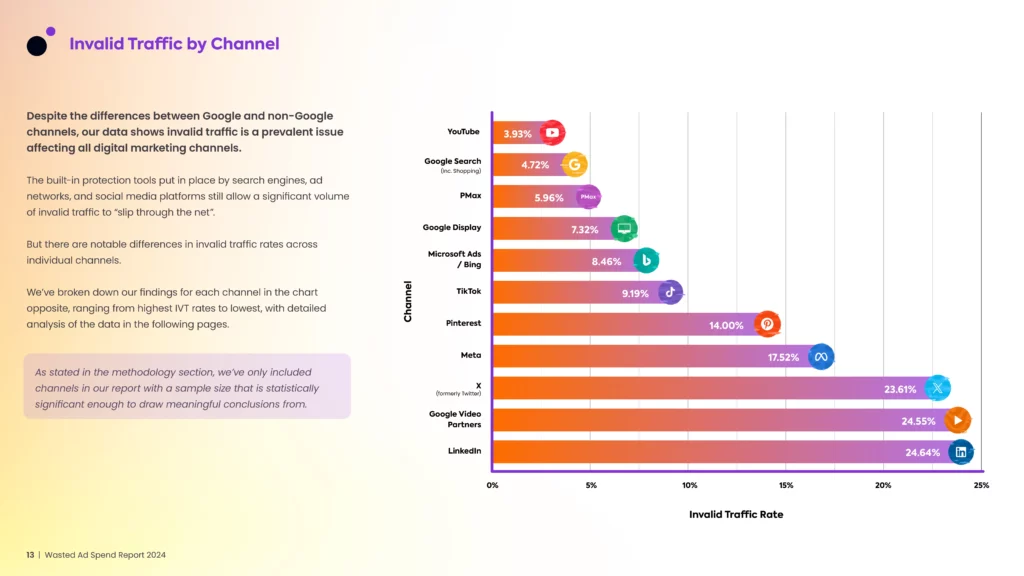

- Lunio’s Wasted Ad Spend Report 2024 (produced in collaboration with IAS and Scope3) claimed that “[w]e evaluated a sample of more than 2.6 billion paid ad clicks…over the course of twelve months (May 2022 — May 2023)… 8.5% of all paid traffic was invalid”. They further estimated that about $55 billion had been lost due to what they term “invalid traffic” (IVT) in 2022, and predicted that about $71 billion in online ad-spend would be sacrificed to IVT globally in the coming year.

- This last example was notable for having made some serious attempt at quantifying the prevalence of fraudulent ad-spend per digital advertising platform, as shown below:

2: Consent Management

The ongoing public and technological shift towards “privacy by design” is rapidly obsoleting many of the methods that digital marketers have traditionally depended on to gather deterministic data and feedback on their work and its impacts, whether for the purposes of planning, designing, executing, improving, or reporting on that work. This has been terrific news as far as human societies are concerned, but for us digital marketers, it has presented certain headaches.

Here’s one: I have observed that it is now fairly common for ~15-40 per cent of a given advertiser’s “ad clicks”, as reported by Meta Ads Manager (I’m referring to the ‘link clicks‘ metric here), don’t result in any attributable “landing page view”, as reported via the Meta Business Tools. To be clear, it is still readily feasible to achieve higher “ad-click-to-landing-page-view” ratios than that; it’s also true that some variance between the two metrics is normal, and otherwise explicable. However my recent experience has been that most marketing stakeholders remain simply unaware of any such degradation in “signal quality” over recent months and years. And even in those cases where the relevant stakeholders are awake to these changes, then more often than not they have not yet invested the time and resources needed for repairs. Not yet.

Many of the key events and milestones in the global uptake of “privacy by design” principles have occurred since 2018, when the EU’s “General Data Protection Regulation” (GDPR) came into force. I have already written at length (in this post) on the parallel histories of Canadian and European data privacy laws, and while I’m still quite happy to recommend that post to anyone curious, I do have some notes for myself, in hindsight:

- One thing I got right was how the GDPR had established a much higher threshold for what constitutes “valid consent” to one’s personal data being collected and/or used by digital services. The law accomplishes this by defining “consent” as… erm… well, consent. By contrast, digital publishers and marketers have traditionally relied upon a basis of “implied consent” for their various data-harvesting business practices, for marketing (and other) purposes. As you are no doubt aware, “implied consent” is, and always was, just bullshit.

- One thing I would’ve gotten right, but didn’t really explore was the way Big Tech (but also Small-to-Mid-Sized Tech) responded to GDPR, in essence, by turning around to their customers and saying “right, our systems fully comply with all global privacy laws, just as long as you never send anything to them or do anything with them that would violate any relevant privacy laws, so please tick this legally-binding checkbox confirming that you’ve promised that you’ll never ever do that”. This legal sleight-of-hand has enabled firms such as Google or Meta to continue offering (more or less) the same digital marketing toolsets as before, while offloading and transferring much of their own liability risk onto their customers.

- One thing I got wrong was my prediction that “data rights” would make their way into the broader public debate surrounding the 2019 federal election. My contention had been that any party forming government in Canada would be obliged to adopt GDPR-like protections at the federal level, or else risk losing access to EU markets. In actual fact, five years later a watered-down version of the GDPR is still toddling its way through Parliamentary committees, and it’s anybody’s guess as to whether the bill will pass before the next federal election call. In short, we still haven’t done anything. I dared to hope that we might’ve.

The next “shock” for most Canadian marketers on the data/privacy front is likely to be Google’s roll-out of “Consent Mode v2”, which will become became compulsory in March 2024 for all Google Ads customers subject to Google’s “EU user consent policy” (which is to say, a lot of us). As one very new support doc in Google’s Tag Manager Help Center explains: “To keep using measurement, ad personalization, and remarketing features, you must collect consent for use of personal data from end users based in the EEA and share consent signals with Google”.

Next year, in early March, the Digital Markets Act (or DMA) will impose new obligations on large digital companies operating in the European Economic Area (or EEA), notably bringing additional consent requirements. In addition, on the platform technology side, we know that third-party cookies have been deteriorating as browsers have been phasing them out, and customers choose not to allow them.

So these regulatory, platform, and technology changes are not “new news”, but 2024 is the inflection point for marketers where your digital marketing and measurement will rapidly lose effectiveness and functionality if you don’t take action.

— Jane Lascelles, EMEA Regulations Program Manager, Google Marketing Platform, November 28th, 2023

This is, of course, a valid and altogether reasonable request for Google to make. The real trouble will only come once an overwhelming majority of Canadian marketers come to realise that in order to do so, they must now undertake several years worth of long-deferred “data stewardship” work within critical project timelines that will be measured in weeks, if not days. Regarded as a class, I would hazard that the ‘average‘ Canadian organisation today is one full decade behind the “state of the art” with regard to privacy compliance and corporate data governance. Much of the knowledge work necessary for adapting to this nascent, privacy-preserving Web remains incomplete. Our circumstances are — in a word — pitiable.

3: Third-Party Data (or ‘Garbage In, Garbage Out’)

In addition to its impacts on deterministic data (most often gathered in a “first-party” context), another natural consequence of the uptake of “privacy by design” has been the step-change deterioration in signal quality for virtually all forms of probabilistic audience data (often gathered in a “third-party” context). Yet despite this, probabilistic data continues to inform most of the key decisions digital marketers make every day — about media budgets, about campaign strategy, about audience targeting, and so forth.

One would think that this should be (or have been, by now) a much bigger problem than it has turned out to be, in practice. To put it bluntly: if the audience data is all garbage, as I am asserting that it is now, then why haven’t more people been noticing?

This is perhaps a fitting time to bring up the compelling, peer-reviewed evidence (published five years ago) suggesting that third-party audience data tended to be only slightly more accurate than random selection, even when segmenting users along fairly basic demographic factors, such as age and/or gender cohort. And that’s to say nothing about the accuracy (or utility) of the many, more granular “interest-based” segments offered by data brokers all across the programmatic marketplace.

In other words, yes, emerging technical and regulatory constraints have made user tracking and data-collection more challenging, but any impacts to the efficacy of third-party data segments has been hard to notice, because these data segments were already garbage.

The reasons for this are complex and manifold, but my personal favourite explanation comes midway through an October 2020 episode of the wildly niche podcast “What Happens In AdTech“, in an episode featuring Pontiac Intelligence CEO Keith Gooberman. The key bit comes at 17:00 – 22:15; the clip below should start right about there, and I’ve transcribed it for you below. The fellow who tees him up at the beginning of this clip is Ryan McConaghy, formerly(?) behind What Happens in Ad Ops and currently “VP, Global Monetization Strategy” at Condé Nast.

Companies start, these data companies. So they realise through cookies that they can cookie all types of sites, and find out all types of detail of the users that come through there, and segment them. Okay, so this is as remarketing and third-party data, this is getting going 2005-10, they’re starting to realise what they can do. Big cookie footprints. Okay.

So let’s take one of these companies that started out in the data, DMP space, okay? They already raised $50-$100 million. They’re already in debt. It’s a venture play, venture money behind it, they’re down $100 million. Okay? So, if you’re down $100 million, you’d better build yourself a scalable business. You can’t just build a business that makes $1 million a year and be like “We did it!”, right? It’s like “No no, sir, we’re gonna need a bigger business than that. You took a hundred million of our dollars”.

…So let’s say one of these companies, these early DMPs, okay? They go to all the car websites. So they go to KBB[.com], Edmonds[.com], and Cars[.com], and they say “Hey, I got a proposal for ya. I’m gonna put a pixel on your site. We’re gonna collect data of who looks at a Mercedes S-Class. We’re gonna turn around, we’re gonna sell the data to BMW and Mercedes, we’re all gonna share the money, everybody goes home happy.”

The car websites are like “Yes! What a great idea! No more ads! I love it, pixels, all day, let’s go”. They then do this, okay? They get all the pixels down. And they get an audience together of people that’ve looked at the Mercedes-Benz in the last three weeks, on all these major car retailers, okay?

And they package the audience, and then they go to BMW, and they get their agency to buy against this audience, okay? They do it, they do the whole thing. The agency says “Yes, sounds interesting. Let me test $25,000 against this, okay? I’ll test— I’ll pay, I’ll put $25,000 into the media buy, I’ll pay ya $3,000 for the data”, okay?

So they run the campaign. It’s the best performing campaign that BMW has ever run on display ads, ever. It’s unbelievable! It’s the greatest thing they’ve ever seen! They’re like “This is amazing!”. They’re like “Hey, we did $25,000 last month. Let’s do $250,000 this month”. And the data guy, salesmen, you know these people, right? He’s like [rubbing hands together] “ohh mmy ggoo, oh, YES!“. Like, “Turn it UP!“.

So he goes back to the AdOps department, okay, the AdOps, y’know… these are the people like us, who’re sittin’ there, looking at the numbers. And they’re like “I got BMW, they want every person who’s looked at a Mercedes, give ’em all three million cookies so they can do this buy!”.

And the data guy sits there, and he’s like [mimics typing]: “…nah, forty-seven thousand, bro. Only 47,000 people looked at the Mercedes.”

And he’s like, “No no no, I need three million, I need three million! That’s… they’re not gonna be able to spend more” — are you ready for the punchline? — “they’re not gonna be able to spend more than $2000 with us a month if we only have forty-seven thousand”. And the data guy goes, “Uhh, I can’t make up people who like Mercedes. You said you wanted people who like Mercedes!”.

And what do you think happened in that room? You think that they ended up serving three million cookies that included anybody that’s ever looked at a car, and other people that they could find that fit the description, so they could sell it through to the client? Or you think they held true to word, and only gave ’em the Mercedes audience?

…The joke is, is that the CEO who raised $100 million was like “I can’t, I can’t make enough money back if it’s not, if we don’t, if we don’t dilute these audiences. I can’t make this work if we don’t dilute the audiences“. And that discovery, my friend, there’s your reason why all the audiences are worthless. I get it! Listen, people look at cars. You know how many people are in the “auto intender” audience in most of these things? 144 million cookies. I’ll tell ya, it’s a big business. It ain’t that big of a business.”

— Keith Gooberman, CEO, Pontiac Intelligence

4: Recommender Discrimination Systems

The choices an online publisher makes about the content they will present (or “surface”) to a given user are the most direct and effective lever they have available to them in order to influence how that user “engages” with their platform – and thus, to engineer their own profitability. The algorithms tasked with making such decisions on behalf of publishers are termed “recommender systems“, but insofar as these work to monopolize an ever-greater share of each individual user’s attention, in pursuit of maximising the online publisher’s profits, these might more usefully be termed “discrimination systems” — for the sole animating purpose of such a system is to mark a population of users out from one another.

In order to better predict what sorts of content will keep a given user “engaged” (and thus eligible to be advertised at), such systems might run experiments by presenting some “test subjects” (that is, you or I) with some given stimuli, then observing their reaction (or lack thereof), and noting the results for future study. The accuracy of such predictions tends to improve as the scale of experimentation increases; so too does their potential to logically segment and stratify users on the basis of some shared set of observable data-traits. This process goes on continuously and forever — or at least, the machines that do this work are often designed so as to assume it will. That is the essence of the wargame in which our individual minds now engage, against sophisticated networks of computers programmed by one or more teams of clever and well-funded domain experts, each time we thumb idly through our various digital “feeds”.

What these systems tend to work out, of course, is how the content which best captures our attention — and this is essential: within the contexts they have been tasked with “optimising” — tends to be strongly emotively charged. “Fight, flight, or freeze”-type stuff. And so these systems can, and often do, become adept at surfacing content that prompts us to feel angry, or sad, or happy, or any number of more (and less) nuanced emotions. They also show an exceptional knack for doing so just as our own, individual attention threatens to wane. In doing so, the algorithm succeeds in winning one more engagement, one more tap or swipe, and possibly another one after that. In these respects, recommender systems perform superlative work.

Alas, there are other, peskier dimensions of human psychology with which recommender systems would seem to have proven less helpful. They have shown a proclivity for inspiring body dysmorphic disorders in children, and for amplifying and overindexing extremists and other “fringe” perspectives. At a population level, their widespread deployment has had the general effect of fracturing our civic spaces, corroding our politics, and degrading our mental health. Many would consider these to be negative aspects of such systems; the sort of thing that’s people ought to look into, and perhaps correct somehow. Unfortunately, there is little seeming overlap between this growing body of thought and the profit-driven actions and motives of those digital publishers who employ them.

To our great and well-deserved shame, the same must also be said of advertisers — yes, us — who blithely encourage the pervasive and uncritical deployment of such systems, whose workings we do not and cannot even claim to fully know, in the hopes of realising an ever-greater supply of ever-more granular ad inventory, addressable to the individual consumer’s mind, with ever-greater accuracy and precision.

5: Generative AI-yai-yai

…Look, you really don’t need me to churn out any more words on the potential impacts of “generative AI” tools on Field X , do you? Please, let’s just assume that you’d rather I didn’t, and say only that the advent of large language models (LLMs), deployed at societary scale, is likely to exacerbate all of the problems I’ve just listed above.

That’s not to say that the technologies themselves are nefarious (Beer would surely object to that premise), even if there are compelling arguments that the most popular and visible contemporary AI systems definitely are. What I am suggesting is that among the “first movers”, the most enthusiastic adopters of generative AI technologies, will likely be those who seek to leverage them towards nefarious purposes. I should imagine that a great many of them shall do quite well for themselves, for a time.

Variety: the Spice Melange of Life

While I promise to try not making a habit of this, there are times when any further editorialising on my part would only serve to muddle the meaning of my source. So, in much the same way that this post began with me quoting far too much from Beer’s first lecture, I’d like to end it by quoting far too much from his second. Ahem:

Our culture has had nearly 300 years to understand the problems of Newtonian physics. It has had more than half a century to get its grip on relativity theory and the second law of thermodynamics, knowing that it is at any rate possible to make general statements about the physics of the universe. Not all of us, I dare say, would care to answer basic questions about these two, although one might have supposed that the culture would have imbibed them by now. The observed fact is that the culture takes a long, long time to learn. The observed fact also is that individuals are highly resistant to changing the picture of the world that their culture projects to them.

I am trying to display the problem that we face in thinking about institutions. The culture does not accept that it is possible to make general scientific statements about them. Therefore it is extremely difficult for individuals, however well intentioned, to admit that there are laws (let’s call them) that govern institutional behaviour, regardless of the institution. People know that there is a science of physics; you will not be burnt at the stake for saying that the earth moves round the sun, or even be disbarred by physicists for proposing a theory in which it is mathematically convenient to display the earth as the centre of the universe after all. That is because people in general, and physicists in particular, can handle such propositions with ease. But people do not know that there is a science of effective organization, and you are likely to be disbarred by those who run institutions for proposing any theory at all. For what these people say is that their own institution is unique; and that therefore an apple-growing company bears no resemblance to a company manufacturing water glasses or to an airline flying aeroplanes.

The consequences are bizarre. Our institutions are failing because they are disobeying laws of effective organization which their administrators do not know about, to which indeed their cultural mind is closed, because they contend that there exists and can exist no science competent to discover those laws. Therefore they remain satisfied with a bunch of organizational precepts which are equivalent to the precept in physics that base metal can be transmuted into gold by incantation—and with much the same effect. Therefore they also look at the tools which might well be used to make the institutions work properly in a completely wrong light. The main tools I have in mind are the electronic computer, telecommunications, and the techniques of cybernetics. . .

Now, if we seriously want to think about the transmutation of elements in physics, we will recognize that we have atom-crackers, that they will be required, and that they must be mobilized. We shall not use the atom-crackers to crack walnuts, and go on with the incantations. But in running institutions we disregard our tools because we do not recognize what they really are. So we use computers to process data, as if data had a right to be processed, and as if processed data were necessarily digestible and nutritious to the institution, and carry on with the incantations like so many latter-day alchemists.

The invitation to face up to these realities is a necessary one if there is to be any real chance of perceiving the proper role of currently available tools. For it is not something scintillatingly clever that I am proposing, not a complicated new extension of mind-blowing techniques that are already beyond most people’s understanding, not a “big brother” that will alienate us still further from the monstrous electronic machinery that by now seems to govern our lives.

I am proposing simply that society should use its tools to redesign its institutions, and to operate those institutions quite differently. You can imagine all the problems. But the first and gravest problem is in the mind, screwed down by all those cultural constraints. You will not need a lot of learning to understand what I am saying; what you will need is intellectual freedom. It is a free gift for all who have the courage to accept it. Remember: our culture teaches us not intellectual courage, but intellectual conformity.

Let’s get down to work, and recall where we were. A social institution is not an entity, but a dynamic system. The measure we need to discuss it is the measure of variety. Variety is the number of possible states of the system, and that number grows daily, for every institution, because of an ever-increasing range of possibilities afforded by education, by technology , by communications, by prosperity, and by the way these possibilities interact to generate yet more variety. In order to regulate a system, we have to absorb its variety. If we fail in this, the system becomes unstable. Then, at the best, we cannot control it- as happened with the bobbing ball on our elaborated tennis trainer; at the worst, there is a catastrophic collapse -as happened with the wave.”

— Stafford Beer, “Designing Freedom”, p. 11-12 [emphasis mine]

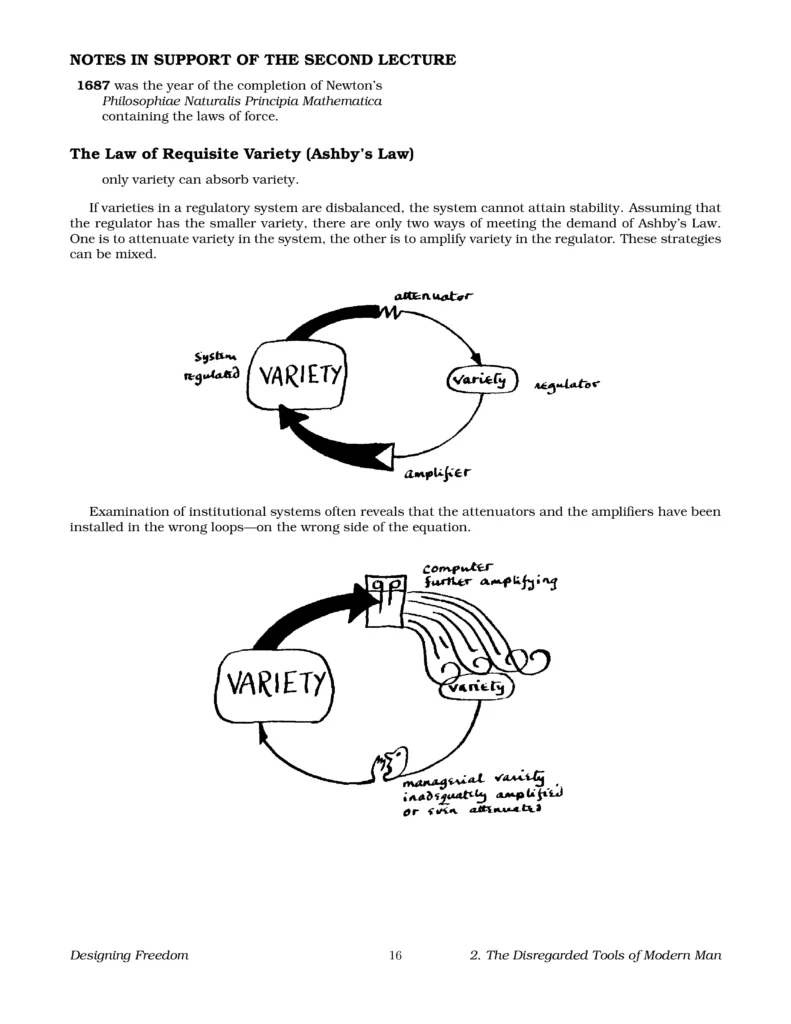

I have already suggested a list of three basic tools that are available for variety amplification: the computer, teleprocessing, and the techniques of the science of effective organization, which is what I call cybernetics. Now I am saying that we don’t really use them, whereas everyone can assuredly say: “Oh yes we do.” The trouble is that we are using them on the wrong side of the variety equation. We use them without regard to the proliferation of variety within the system, thereby effectively increasing it, and not, as they should be used, to amplify regulative variety. As a result, we do not even like the wretched things.

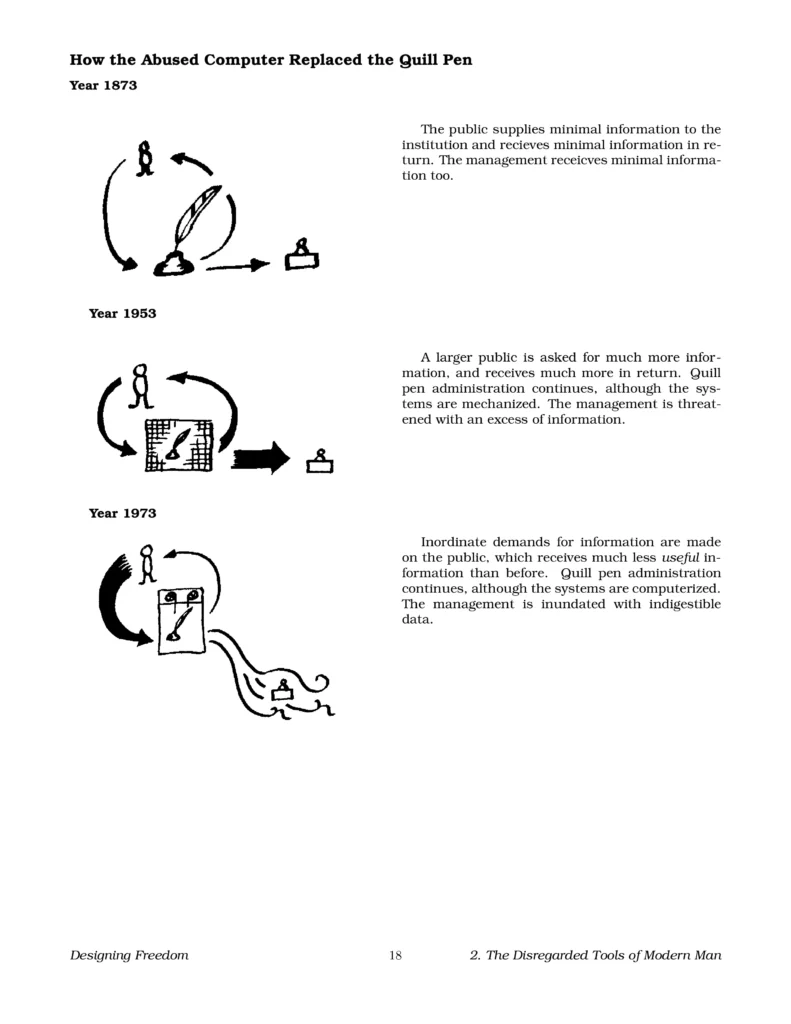

[…] It’s obvious really, once the concept of variety and the law of requisite variety are clear. The computer can generate untold variety; and all of this is pumped into a system originally designed to handle the output of a hundred quill pens. The institution’s processes overfill, just as the crest of the wave overfills, and there is a catastrophic collapse. So what do we hear? On no account do we hear: “Sorry, we did not really understand the role of the computer, so we have spent a terrible lot of money to turn mere instability into catastrophe.” What we hear is: “Sorry, but it’s not our fault—the computer made a mistake.”

Forgive my audacity, please, but I have been “in” computers right from the start. I can tell you flatly that they do not make mistakes. People make mistakes. People who program computers make mistakes; systems analysts who organize the programming make mistakes; but these men and women are professionals, and they soon clear up their mistakes. We need to look for the people hiding behind all this mess; the people who are responsible for the system itself being the way it is, the people who don’t understand what the computer is really for, and the people who have turned computers into one of the biggest businesses of our age, regardless of the societary consequences. These are the people who make the mistakes, and they do not even know it. As to the ordinary citizen, he is in a fix—and this is why I wax so furious. It is bad enough that folk should be misled into blaming their undoubted troubles onto machines that cannot answer back while the real culprits go scot free. Where the wickedness lies—and wickedness is not too strong a word—is that ordinary folk are led to think that the computer is an expensive and dangerous failure, a threat to their freedom and their individuality, whereas it is really their only hope.

There is no time left in this lecture to analyse the false roles of the other two variety amplifiers I mentioned—but we shall get to them later in the series. For the moment, you may find it tough enough to hear that just as the computer is used on the wrong side of the variety equation to make instability more unstable, and possibly catastrophic, so are telecommunications used to raise expectations but not to satisfy them, and so are the techniques of cybernetics used to make lousy plans more efficiently lousy.

— Stafford Beer, “Designing Freedom”, p. 14 [emphasis mine]

Well, you’ve heard the fellow. In Part III (stay tuned!), I still intend to focus on the fourth of Beer’s lectures, titled “Science in the Service of Man“. In this post, I’ve mainly focused on the problems facing digital marketers right now, as we enter another new year. In the next one, I want to explore what I see as their underlying causes, and why — despite their solutions being relatively obvious — any durable “fix” remains unlikely, barring some dramatic shift in the prevailing industry paradigm. And, because I’ve now managed to go some 10,000 words without making a direct reference to Project Cybersyn (which, holy shit you guys, Project Cybersyn!!), I’ll try to work that in somewhere too.

Thanks for reading,

-R.